Han Kang's Nobel prize win sheds light on Gwangju uprising, a dark chapter in South Korean history

For Han Kang, Gwangju became another word for the two extremes of humanity: the sublime and the horror.

In short:

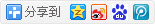

Nobel prize-winner Han Kang's novel Human Acts was inspired by the trauma of the 1980 Gwangju uprising.

Survivors of the massacre hope her work will reveal to a global audience the sacrifices they made for democracy.

What's next?

Han's latest novel — which will be published in English next year — covers a similar instance of historical pain in Korea, with a focus on the Jeju Island uprising.

When Han Kang was nine years old, a massacre of civilians by soldiers in her hometown of Gwangju drastically reshaped the course of South Korean history.

Sometimes referred to as the Tiananmen Square of Korea, the 1980 Gwangju student uprising and subsequent mass killings were the subject of her acclaimed 2014 novel Human Acts.

Han this month became the first Korean to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Human Acts gives a harrowing account of a defining moment in South Korea's struggle for democracy.

Eyewitnesses and survivors of Gwangju welcomed the accolade, hoping it would help bring a previously hidden history to a global audience.

But Han is not the first to write about the atrocities that occurred in Gwangju — and those who came before her faced incredible risks.

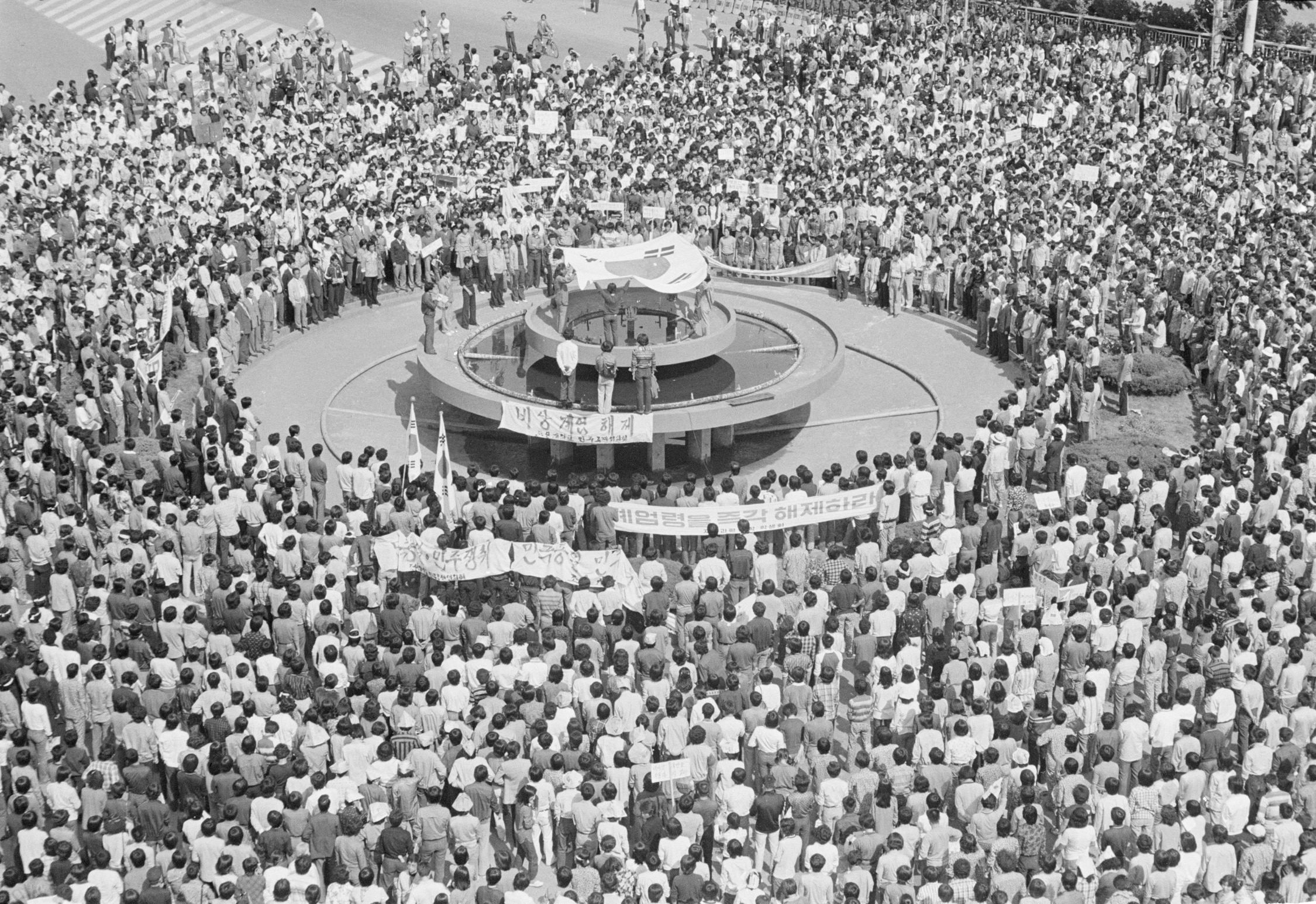

One of them is writer and eyewitness Lee Jae-eui, who said what made Han's Human Acts so powerful was the Nobel laureate's ability to viscerally echo aspects of his own experience.

"The foul smell of the rotting corpses is still strongly etched in the deepest part of my brain," Lee said.

The Gwangju uprising is sometimes described as South Korea's Tiananmen moment.

What happened in Gwangju

In mid-May 1980, South Korean society was in the grip of military dictator Chun Doo-hwan.

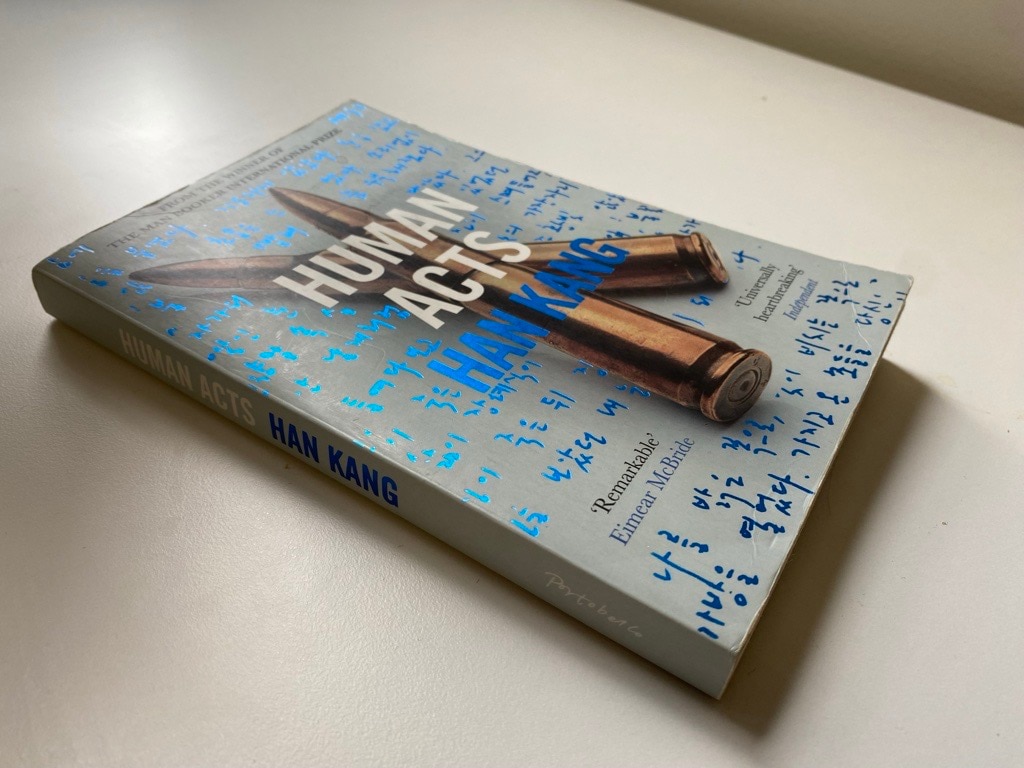

Fed up with living under martial law, students peacefully protested on the streets of the working class city Gwangju calling for Chun to step down.

The military regime responded with force on May 18, in an operation chillingly codenamed "Splendid Holiday".

Thousands of soldiers were deployed.

Students and citizens gathered to call for an end to military rule in South Korea in 1980.

They beat, shot and arrested protesters while helicopter units gunned down citizens from the air.

Other Gwangju locals joined the students and armed themselves before soldiers suppressed the uprising.

Within 10 days at least 166 people were killed by the military, according to a truth commission established in 2020, although the numbers are contested and estimates vary.

The commission found dozens more were missing — presumed dead — and more than 2,600 were wounded.

A mural shows Gwangju citizens donating blood to the injured protesters.

Park Kang-bae was a 17-year-old high school student who witnessed the events unfold.

For Mr Park, the starkest memory is of bodies piled up in the local gym.

"I still can't forget the screams of the families who found the bodies," he said.

"Citizens demanded democracy, but soldiers suppressed it by force, killing and injuring many people — and the wounds have not healed so far."

The massacre has left deep emotional scars for the families of the victims.

Lee, the author, recalled hiding in an alley as snipers opened fire on his fellow protesters.

"About 10 metres away, in front of me, a young man was shot and lay bleeding. He shivered for a moment, then went limp," he told the ABC.

"As I watched the dying people, my anger soared, and I couldn't stop the tears from flowing."

The secret manuscript

Lee managed to escape before the military finally quashed the uprising, but a deep sense of survivor's guilt later motivated him and some collaborators to document the brutal events.

Lee Jae-eun said he had goosebumps after reading a passage in Human Acts that mirrored his own experience.

Along with collaborators, he began compiling testimonies from survivors into a book.

"The Chun Doo-hwan military regime thoroughly blocked the truth about the massacre from being known to the outside world," he said.

"For this reason, documenting and publishing this book was a life-threatening task."

Some who helped gather testimonies from survivors and collect evidence were tortured and imprisoned, he said.

His book — Gwangju Diary — was initially published in 1985 under the name of a renowned Korean novelist.

Not until decades later was Lee revealed as the real author.

The publisher was arrested and copies were confiscated, but the clandestine manuscript was circulated underground.

Lee said the book became a "thorn in the side of the military dictatorship", which gave in to people's demands for democratic elections in 1988.

Unearthing a hidden history

South Korean historian Se Young Jang said the history of Gwangju had a universal message.

"Gwangju uprising was not an isolated tragedy which happened in Korea," she said.

"This type of state violence is happening or could happen in any other parts of the world."

Dr Jang, a senior research fellow at the University of Vienna, pointed out that longstanding censorship and previous conservative governments had meant the experiences of Gwangju victims were not properly investigated for many years.

The names of the victims are etched into the wall of a monument in 5.18 Memorial Park in Gwangju, South Korea.

The Chun regime had promoted a false conspiracy theory about North Korean involvement in the pro-democracy protests.

It wasn't until 40 years after the event that a truth commission was established, although Dr Jang said some Gwangju civil society groups remain unsatisfied with its findings.

And it took decades for official acknowledgement and apology for sexual violence by soldiers during the uprising.

Humanity's extremes

For many, Gwangju has emerged as a symbol of democracy.

But for Han Kang, Gwangju became another word for the two extremes of humanity: the sublime and the horror.

"I can see everywhere Gwangju whenever we are confronted by these two extremes," she said in a 2020 interview.

Many hope Han's Nobel prize will spread greater awareness of Korea's traumatic history.

Han's family had left Gwangju just months before the crackdown, and like Lee, she felt a sense of guilt.

"It was the feeling that some people were hurt instead of us," she said.

Han recalled overhearing hushed conversations between her parents while she peeled garlic in the kitchen as a child — and was deeply affected by a photograph she saw of a young woman killed during the uprising.

For Jay Song, from the Korean Research Centre at Curtin University, Human Acts encapsulates "han" — a Korean emotion with no direct translation in English.

"'Han' means a deep sorrow and a deep sense of injustice … it's the sense of helplessness and restlessness," she said.

Academic Jay Song says Han Kang's prose has resonated with non-Korean speakers.

Dr Jang said Human Acts transported readers "into the souls of those victims".

She added Han's most recent novel, We Do Not Part, which is set to be released in English next year, tackled a similar historical tragedy of state violence — this time focusing on the Jeju Island uprising and massacre in the late 1940s.

Professor Song said Han's Nobel win would also give people "a deeper understanding of Korea".

"It's not all about this shiny, bling-bling K-pop and bright lights in Seoul," she said.

"There is that very dark side … It's not really a distant history."

By:https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-10-27/han-kang-nobel-win-spotlights-gwangju-uprising-korea-human-acts/104470352(责任编辑:admin)

下一篇:American voters on both sides hate their political system — so why does it keep getting worse?

Socceroos rescue a point

Socceroos rescue a point  Wallabies thrash Wales 52

Wallabies thrash Wales 52 Jake Paul beats Mike Tyso

Jake Paul beats Mike Tyso Live updates: England vs

Live updates: England vs  US election 2024: Donald

US election 2024: Donald  US election live: Kamala

US election live: Kamala

- ·North Korea's latest weapon agains

- ·Hezbollah says Israel 'cannot impo

- ·Inside the rise of US oligarchs and how

- ·Thailand's worst suspected serial

- ·Tabi shoes are turning heads from Holly

- ·FBI arrests Florida man planning attack

- ·Illegal immigrant gets life sentence fo

- ·Bibles, water, watches and sneakers: Do

- ·North Korea's latest weapon against

- ·Hezbollah says Israel 'cannot impose

- ·Inside the rise of US oligarchs and how i

- ·Thailand's worst suspected serial ki

- ·Tabi shoes are turning heads from Hollywo

- ·FBI arrests Florida man planning attack o

- ·Illegal immigrant gets life sentence for

- ·Bibles, water, watches and sneakers: Dona

- ·US to give Kyiv anti-personnel landmines

- ·An arrest warrant for Benjamin Netanyahu

- ·One of Vietnam's high-profile politi

- ·Shanghai Walmart Attack: A Man Randomly S

- ·South Korean police officers jailed over

- ·Cambodia publicly shames maid deported af

- ·North Korea to use all forces including n

- ·Philippines condemns China attack of Viet

- ·US adds 2 more Chinese companies to Uyghu

- ·North Korean defector steals South Korean

- ·Malaysia deports Cambodian worker for cal

- ·Rebels battle for Myanmar junta’s weste